New rock route in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca

I’m writing this from an idyllic base camp underneath some of the most spectacular unclimbed mountains I’ve ever seen. The campsite is flat and grassy, next to a soothing stream and above us is a scene of Andean wonder…

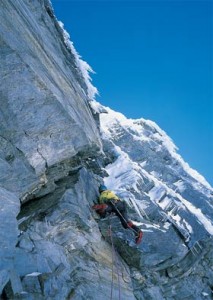

Photo: Jim Sykes belays Tony Barton on the first ascent of ‘Cop Out’ on Huaytapallana 2 (5025m), The Cordillera Blanca, Peru.

When people first visited the Alps (some time around the ‘Romantic’ period when folk first got a taste for the mountains) they were so over-awed by them that they used mirrors to look at them. We don’t do that any more, but looking at these monsters, you can maybe understand why. We are camped in the Cordillera Blanca, near the West side of Huascaran (Peru’s highest mountain) and above the area you find the ice collectors that you might have read about in my previous entry.

For our (Barton and Metherell) first attempt on the mountain we are joined by Jim Sykes and assisted with mule hire and charming base camp guards by Charlie Good, the owner of the shiny new Llanganuco lodge, an up-scale mountain lodge that has is located at the road head. With its charming and immaculately dressed owner, the ‘Casa de Charlie’ is the most spectacularly located lodge (the views from the manicured lawns are remarkable) and it has some of the atmosphere of what I imagine it would feel to visit a genteel coffee plantation of the type that you would find in the pages of ‘Out of Africa’. So yeah, it is definitely one of the more unusual places for you to enjoy your cup of perfectly brewed PG Tips.

Photo: ‘Shackleton’ (a Rhodesian Ridgeback) outside his home: The Llanganuco Lodge

Who am I climbing with? Tony Barton is a 41 year old resident of Fort William and he’s done 7 full seasons in Peru. He’s an experienced mountain guide and is married to a local called Rocio. Massive thanks to her for helping us out with getting the logistics sorted.

We’re joined by Jim Sykes, a mountain guide, musician, film-maker and Huaraz resident who is also married to a Peruvian. Last year, they were both active in this area, climbing a stunning new route up Huaytapallana 1 (H1) that went at about VS/Severe.

This week we are here for perhaps slightly steeper challenges and to be honest, I’m kind of nervous about being on the rock again. I’ve been completely focused on mixed climbing for the past three years and I haven’t climbed a route of what the man who wrote The Eiger Sanction described as ‘The Sixth grade’ for longer that I’d like to admit.

But at least we know that the rock is good, and that there will be some gear. Jim has swung leads with American climbing legend Fred Beckey, so it is good to have someone of his calibre on board. He’s also very familiar with the area, doing the camera work for ‘Shika Shika’, a film about the ice collectors who work on the glacier below where we are camped. The ice collectors have a dangerous job which involves working underneath a dangerous serac to collect glacial ice for the upscale restaurants. Sykes and his fellow film maker Steve Hyde are keen to get Shika Shika featured at the next LLMF and GMFF so we’re hoping to showcase it at the next film festivals in London and Glasgow.

We spend the day reconnoitring the area. Sykes is a resident of Huaraz (3,500m) with a sideline in fell running. Except the fells out here are involve passes that are higher than the summit of Mont Blanc. So he is just unbelievably fit, striding off on this mile-eating, Dougal Haston stylee stride, leaving me and Barton gasping in his wake. After we’ve walked up to a pass at 4900 we go to look at Huaytapallana 2 (5025m). Well, to be honest, Jim and Tony go. I lie horizontal on the ground round the corner from the peak feeling a bit overwhelmed by the altitude.

The next day, in the cold of the dawn, we’re climbing at last. Jim gets the first three pitches up the slabs and then it is my turn. The sun is warming my back, the climbing is hard, technical, and makes me pant like a racehorse. But the winter spent doing pull up competitions with Fiona Murray and half the summer spent training with Greg Boswell, (a climber and ex wake-boarding champion who is nearly half my age!) were not in vain. I’m not exactly cruising, but upward progress is being made.

Then it is Tony’s turn. The psychological crux on the seventh pitch is his; a dangerous move above a hopeless piece of gear: Nice one. While Tony has been doing this me and Jim are getting anxious. It is already 2pm. We’re nearly half a km off the ground and the belays have been a bit tricky.

Descending from this would be possible, but tricky at best: Decision time. Tony is up for gunning it to the summit and then rapping the North face in the dark. Me and Jim reckon that it is turn around time. We compromise and decide to just follow the line of least resistance up the face, and only head for the summit if there is time.

My turn back at the sharp end. The route kicks back. I red line my breathing and floor it to the skyline ridge. We’re back to ‘normal’ alpine climbing. Stunning views, feeling the go rope heavy after 50m, placing maybe just a couple of runners a pitch and gasping for air in harsh afternoon sunshine. Three pitches later and we’re at the summit ridge. I try to force the route along the ridge but a gendarme (rock pillar) stops me and we decide to abseil off down the North Face.

Basically, because of the shape of the mountain, the North Face is much shorter than the West Face, maybe half the height. Tony organises the abseils. Long swooping drops down perfect sheer walls of clean granite and as night falls we get back to the sacs. Here’s the route description and technical grades:

Cop out

An attempt on the west face which traverses left below the summit ridge. One obvious feature on the lower half of the face is a white vegetated crack and groove.

VI, TD+, 500m, VI, E1 5a

1. 60m, 4b, Start in a niche below grassy crack. Climb slabs and aforementioned crack, and short corner to belay

2. 55m, 4b, Climb directly to a bay below an obvious white vegetatedcrack and groove

3. 50m, 4b, Bear right climbing slabs to gain short corner / groove to belay below steep bulge to the right of the white vegetated crack / groove

4. 60m, 5a, continue directly following slabs and grooves

5. 50m, 4c continue directly following slabs and grooves

6. 60m, 4c, climb slabs to corner, surmount this, follow more slabs to belay

7. 60m, 5a, step left from belay and follow slabs to obvious corner.Climb this and bulge to the top, (serious) to belay

8. 45m, 4a, follow easy ground bearing slightly left

9. 60m, 4a, bear left traversing slightly to gain notch in ridge

10. 60m, 4b, follow ridge to below steep tower

From this point there was one short abseil to the edge of cliff and rappel (3 abs, 60m rope) down the north face. Descend to scree slopes and then make two more abseils to the foot of the buttress.

The lure of the summit is irrisistable

So, we’d climbed a new route. But summits count. And this one was still unclimbed. We recovered from all this climbing at altitude in base camp for 24 hours and the next day Jim headed home to catch up on work.

Now it was just me and Tony. We planned to climb the mountain by heading up the spectacular-looking North ridge. However, the weather was not exactly what the French describe as ‘Grand Beau’. Then we had a break in the weather: enough to let us fix ropes up the first two pitches. It rained the next day, but we reckoned we could maybe do something with our penultimate day. The weather was looking good and we were on.

After a bitterly cold 4am start, we were at the col between H2 and H1 by about 7pm, having already completed six pitches. Tony’s feet were in his duvet jacket to keep off the cold. My tactic on this terrain is copied from the front cover of Paul Pritchards Deep Play: a pair of retro leg warmers that I pulled down over my rock shoes when I wasn’t climbing!

The col between the two mountains featured a spectacular giant chockstone. This gave some ‘festive’ chimneying, followed by a tentative climb, just as the sun reached the face, over a rather loose flake. After the bitter cold of the morning the sun felt pretty sweet and after Tony seconded the pitch we stood there scarcely able to believe our luck. Not only were there fairly decent belays, there was almost no loose rock.

The next pitch gave me one of the most memorable rock pitches I’ve ever been on. Alpine exposure. Just enough gear. And perfect clean rock, including a beautiful granite horn that gave the key to this, the crux pitch of the route at about French 6a or British E1.

Two pitches of exciting ridge traverse later and we were the first people ever to stand on the summit. We enjoyed spectacular views, a couple of chocolate bars and then began the long swooping descend on our skinny ropes back to base camp.

Last Exit

TD, 6a, E1 5a, 450m

Technical climbing up the north ridge on excellent rock with spectacular views. Starting from the highest point of the scree slope below the col. The approach to the scree slopes were climbed in two easy pitches from the left hand side of the west face

- 60m, 4a, bear left then follow broad ridge

- 50m, 4b, continue in same ridge to gain left hand of the two faults below the right hand skyline notch

- 60m, 5a, follow fault into gully, steep moves lead to belay below a giant chockstone

- 25m, 5a Surmount chockstone by climbing on its right hand side.Continue slightly right, passing a loose flake, to belay below a steep corner

- 60m, 5a, climb steep slab to left of corner. Follow short walls and slabs to crest of ridge (serious).

- 60m, 4b, continue along ridge

- 60m, 4b, continue along ridge to north summit

Note: The summit block on the south summit remains unclimbed.

Descent. Reverse broken ground near summit for about 15minutes to a large block. Rappel the north face (4 rappels, 60m).

The Plan

When we started on this journey we had no idea how it was going to all turn out. The plan was to traverse the Cordillera Blanca from the East to the West. On the way we would get used to the thin air, hopefully reconnoitre some unclimbed objectives, and if we were really lucky, actually climb something.

You won’t find this trek in any tourist office or on the pages of The Lonely Planet Guide. It’s a long, long way. We were completely alone for four days and we did not see another white face for the 8 days we were making the traverse. It’s pretty much as close as you can get these days to a place where ‘Here be dragons’ is written on the map. Here’s what happened…

Chavin

We took the morning coach from Huaraz (the so called ‘Chamonix of Peru’) to Chavin. With a name like that, I wasn’t sure what to expect. It’s home to a legendary pre-inca temple. Dating from 600 years before the birth of christ, the artwork consists of these spectacular leering gigantic heads, which feature alongside heavily contoured harp-like stone sculptures. The meaning of these pieces, and exactly what went on here is delightfully mysterious.

According to the guidebook, the high priests were were enthusiastic users of hallucinogens and held ceremonies of ‘a very private nature’. Small mortars, possibly used to grind vilca (a hallucinogenic snuff), have been uncovered, along with bone tubes and spoons decorated with wild animals which we associate with shamanistic transformations. Artwork at Chavín de Huantar also shows figures with mucus streaming from their nostrils (a side effect of vilca use) and holding what is interpreted to be San Pedro, a hallucinogenic cactus.

Our hotel takes pride of place at the top of the square, and from its flower-filled courtyard, complete with friendly cat; not destined for the menu as ‘carne’ (meat: origin unspecified) in this particular part of Peru) we could hear the shouts and brawls of what sounded like a fairly major event. Curious, I wander to the source of the noise, pay the entrance fee at the door and enter into an arena that looks like it doubles as the local cattle market.

I have inadvertently stumbled upon one of the seamier aspects of Campesino life: The Saturday afternoon cockfight. There was frantic betting and even more frantic drinking. Almost every male over the age of 18 is focused on getting wacked out of their gourd on lager, and they don’t care if they fall over.

WE stop at the wonderfully named ‘Hotel Rickay’ to savour a last meal before 9 days of mostly de-hydrated food. The place has a vacant, deserted atmosphere, the Pizza could kindly be described as ‘average’. When we hand over a 50 Sole note, and the hotel owner has to go on a frantic search (which includes emptying her own public telephone) to find change for a 50 sole note.

Before the First Pass

Day one gets us most of the way to the pass. On Day two we change horses. Literally, as our Arriero for the first day has to head down to join in the road block. Depending on how cynical you are, this is either a national road block or a beer-festival. Our new Arrieros starts the difficult task of getting the horses to accept our loads. The first horse is reluctant to work, and bolts as soon as our sacs touch its back. The second animal is led to the place where its work starts for the day and a towel round its eyes seems to work wonders on its motivation.

With impressive skill, the Arriero combines pack-horse leading with herding of his hundred-strong flock to the high pastures in the honeyed light of dawn. ‘That lot‘ll snag him a nice wife right enough.’ says Tony.

We are accompanied by three rangy mutts (two tawny brown and identical, and one grey) who appear to fulfill the role of some kind of sheepdog in this operation. However, dogs from this Quebrada (valley) have always under-perfromed in international sheepdog trials.

The curved-backed, grey hound preferred to leave most of the work to the Arriero, trotting casually behind his owner who was working flat out to round up his sheep and drive them up to the high pastures. The other two hounds were in some kind of a state of loved-up bliss. This was both sweet, and also slightly worrying as they looked identical in shape, size and colour. Once we looked around and they were licking each others tongues. ‘They like each other.’ said Tony.

The walk up to the pass in the honeyed morning light was exceptional. Through stunning high sheep grazing pasture, lit by the blue Andean high mountain light and with stunning unclimbed mountains of snow and ice appearing as we climbed higher. When we get to the pass our arriero stops the horse, moves aside some rocks making up a temporary wall to separate his side of the valley from his neighbours and we are on the other side of the pass.

Acclimatisation and a new route

We pitch the tent by a lake at 4650m and breathe thin air for two days. From the campsite a walk to the perfect slab of clean rock is visible on the left hand side of the pass is irrestistable. The base of the crag is at around 4,900m) and we spot a line up weakness up the left edge. Three runners and 45m later, Left Hand Route (Severe) is ours.

The nights in the tent are etched in my my mind and bring forth an involuntary shudder. These are nights at the same height of Mont Blanc, a nightmarish, seemingly endless blur of sharp rocks sticking into the thin sleeping mat, the rasping of our lungs in the thin air, and the fruitless search for a comfortable sleeping position until eventually the 12 hour night pales into dawn and the new day begins. The Andes can be grim, but achingly beautiful.

The mountains here look a bit like gigantic dragons teeth. The sick, twisted forces of endless tropical storms have plastered oceanic quantities of every alpinists worst nightmare on their ridges, faces and summits. They are stacked with objective hazards of every imaginable type. It’s a land of extremes. The silent seracs, the maddest snow flutings, the deepest crevasses. All these things say ‘Andes’ as much as the alps can be described in terms of couloirs, faces and ridges.

Attempt on a Peak

The weather continues to be changeable. Every day the afternoon clouds get thicker and darker. We walk higher, to a high camp at 4,900 below a stunning Andean sharks fin of snow. We prepare for the route, and then the weather breaks. Now there will be snow on the route, and fearful of avalanches, we descend.

The walk out over a second pass under our own steam

We descend from our High Camp to a settlement. Some campesinos are helpful. Others are not. ‘Donkey’s?’ says the female campesino. ‘No, we have Asses.’. ‘Where do I find Donkey’s?’ asks Tony. ‘Over there’ says the campesino, pointing in the vague general direction of the upper half of the valley where there is absolutely nothing to be seen.

‘He would carry out the pearls of Arabia must carry in the pearls of Arabia’ and although we’ve pared our kit to the minimum and eaten most of the our food, our sacks still weigh around 25kg. We’ve been hoping that we could organise some kind of transportation for our kit, but that hasn’t happened. Our only option is to get out under our own steam. Unfortunately for us, this happens to include a 20km hike over a 4,650m high pass.

At 10pm in the evening and glassy eyed with fatigue, we drop down into the village,. The dogs of the town welcome us with a volley of barking. Manfully, I refrain from embracing Tony. Night Coaches grind past with a diesel roar and the corner there is a dimly lit Bodega. We are handed Inca Cola and Packets of Cheese crackers with a gold-toothed smile and we stagger down the street to find a Hotel.

I’ve been acclimatising out here with Tony Barton; the 41 year old Andean guru. He is married to Rocio, a Peruvian, and they are both well cool.

Here’s the plan: Me and Tony are going to spend a month attempting to climb in the Cordillera Blanca. In the meantime, Tom Chamberlain is in Bolivia, trekking with his wife. We will then all go to Lima to meet up and celebrate indepence day on the 28th. Then all three of us are going to the Oriental for an objective that Tony has attempted before.

After one or two minor paperwork issues whose details I won’t trouble you with (Err, thanks Neill), the first trip out here involved getting a collectivo out to the campesino, from where the Andes power out of the Altiplano like a snow-blasted scream set in stone.

What is a Collectivo?

It is a battered Toyota Hi-Ace (no larger than a short wheelbase VW camper van) with seating for 19 (not a misprint). It is the law here in Peru that they must have completely bald tyres and be piloted by a loon. Who drives with an utter contempt; both for his own life – and that of other road users.

Having survived this authentic Peruvian experience we set up camp, completely by ourselves, next to a lake and near an ancient Inca burial site. Lots of skulls in the cave-graves so an unusual place to stay.

On the way we went past Yungay. Joe Simpson writes about this place in one of his books. In 1970 it was the scene of one of the world’s worst natural disasters. There was an earthquake which shook every building in this area to the ground. An entire mountain collapsed on the town of Yungay, burying every single house: Population c. 40,000.

We camped by the lake for 2 days attempting to acclimatise. As usual this involved panting, appetite withdrawal, disturbed sleep and headaches!

Highlights of the trip so far

Not getting food poisoning.

Going to where the ice harvesters work on the glacier below Huascaran (Peru’s highest mountain). They go up there with donkeys and they bring it down to sell it upscale restaurants. Unfortunately, the place where they work is underneath a rather large serac (hazardous ice cliff). It collapsed when they were working in 2003, entombing 15 of them under the ice. Eight of them are still somewhere in the glacier: But you won’t heat tell of this in the places where you see ‘Ice from Huascaran’ on the menu.

Seeing some of Tony’s top secret and completely unclimbed mountains.

We have been accompanied on this, the acclimatisation stage of the trip, by Rocio, Tony’s wife. She’s a local and an all round nice person. It has been great having her explain some of the many and varied strange things that go on on this wild land.

They have organised us rooms in a lovely guest house, with rooftop Andean views, and they have also done a deal with the locals. The locals are going to help us transport all our kit up to the base camp for the next trip, and they are also helping us out with a guard to keep the ‘bandito’s’ at bay.

The guard will bring his own food tho’. Apparently the locals don’t have much of an appetite for the food of ‘Los Gringitos’.

Next Expedition: South America

Tony Barton, Tom Chamberlain and Olly Metherell are off to Peru in July. They plan to spend a month acclimatising before an attempt on a line in the Cordillera Oriental.

Thanks to the MEF, The Sports Council, The BMC and the MC of S for funding.